Evolution Of Inbreeding

It is widely under-appreciated that active inbreeding – and especially biparental inbreeding – can be adaptive and therefore favoured by natural selection. Biparental inbreeding specifically refers to the situation in which two different, but genetically related, organisms breed and thereby produce inbred offspring. This situation differs from self-fertilisation, in which an organism breeds with itself, as is perhaps most commonly studied in plants (e.g., Barrett1996; Vogler and Kalisz 2001). The addition of a second parent complicates how inbreeding will affect individual fitness, partly because we have – by definition – two different individuals to consider (a female and a male), but also because biparental inbreeding can occur between any number of different types of relatives (e.g., siblings, cousins, etc.). I’ll explain these complications in more detail below, but first I want to note two important general points about inbreeding, the combination of which often causes confusion.

The first point is that individuals that inbreed typically produce offspring that have lower fitness than individuals that outbreed (e.g., they have offspring with a lower probability of survival), a phenomenon called ‘‘inbreeding depression’’. That inbreeding depression occurs is well-known, and I won’t get into the details of what causes it (see Charlesworth and Charlesworth 1999; Charlesworth and Willis 2009). The second point is that despite the occurrence of inbreeding depression in inbred offspring, this does not necessarily mean that inbreeding parents have lower fitness than parents that avoid inbreeding. This second point isn’t intuitive, and was first articulated by Geoff Parker (1979) for biparental inbreeding.

Parker’s model of biparental inbreeding

The foundational work of biparental inbreeding theory developed by Geoff Parker appears as a chapter in Sexual Selection and Reproductive Competition in Insects (Parker 1979) [1]. Parker (1979) considered an encounter between, and the subsequent reproductive decisions of, two focal relatives [2]. Below, I’ll show the logic of these reproductive decisions first for females, then for males.

Consider a focal female that can produce n offspring – the exact number doesn’t matter for demonstrating the key point, so to keep things simple, we can start by assuming that this number will always be the same. This focal female encounters a first cousin, and upon the encounter must decide whether or not to inbreed with him. If she does not inbreed with him, then we’ll assume that she is able to find some other male to breed with to whom she is not related. By avoiding inbreeding with her cousin and outbreeding instead, she will produce n offspring that do not suffer any inbreeding depression. For simplicitly, we can set their fitness to a value of 1, and think of this value as the probability that an outbred offspring survives to adulthood. If she instead inbreeds with her cousin, then she will produce n offspring whose survival probability will be reduced by some value δ due to inbreeding depression. Hence, if the focal female outbreeds, then she will produce n offspring with a survival probability of 1. And if she inbreeds with her cousin, then she will produce n offspring with a survival probability of (1 − δ). If we only consider the effects of inbreeding depression, then the n × 1 surviving offspring that the focal female produces by outbreeding will always be favoured by selection over the n × (1 − δ) surviving offspring produced by inbreeding. More formally, the inequality,

n (1 - δ) > n,

will never be satisfied.

But the above inequality leaves out something important that affects fitness given inbreeding. If the focal female chooses to inbreed with her cousin, then his reproductive success will be increased. Hence, by inbreeding, she can increase the reproductive success of her relative, and thereby increase her fitness indirectly – by how much depends on her relatedness to her potential mate. Assuming the focal female is herself outbred (i.e., that her own parents did not inbreed), then her cousin’s relatedness to her will be 1/8 [3]. She should therefore consider any additional reproductive success of her cousin that results from her decision with 1/8 the weight of her own reproductive success [4]. The indirect fitness accrued from the reproductive success of her cousin plus the direct fitness accrued from her own reproductive success defines her inclusive fitness as accrued through her reproductive decision; inclusive fitness, more generally, can be used to determine how selection will act on a phenotype at any given level of biological organisation (Hamilton 1964a; Grafen 2006). In the case of a focal individual inbreeding, we can contrast the inclusive fitness accrued from inbreeding with that of outbreeding,

n (1 - δ) + 1/8 n (1 - δ) > n.

Now, note that the above inequality isn’t always false – as was obviously the case in the first inequality when indirect fitness was not taken into account. If we now imagine a very small value of δ, then the left hand side of the above inequality will approach a value of n + (1/8)n, higher than the inclusive fitness of outbreeding (n). Yet a large value (close to 1) of δ will make the left hand side closer to zero. Whether inbreeding or avoiding inbreeding yields the highest inclusive fitness therefore clearly depends on the value of δ. In fact, we can calculate the threshold value below which inbreeding increases inclusive fitness by isolating the above equation for δ,

n (1 - δ) + 1/8 n (1 - δ) > n

(1 - δ) + 1/8 (1 - δ) > 1

1 - δ + 1/8 - 1/8 δ > 1

1 + 1/8 > 1 + δ + 1/8 δ

1/8 > δ + 1/8 δ

1/8 > (1 + 1/8) δ

1/8 / (1 + 1/8) > δ

δ < 1/9.

In our example, a focal female will increase her inclusive fitness more by inbreeding with her cousin than by avoiding inbreeding with him if δ is less than one ninth – or, put differently, if her inbred offspring have a greater than 8/9 survival probability. A focal female can thereby increase her inclusive fitness if inbreeding depression is sufficiently weak.

We can consider the same interaction from the perspective of the male, encountering a cousin and deciding whether or not to inbreed with her. The key difference from the perspective of the focal male is that inbreeding directly increases his own reproductive success, yielding a higher inclusive fitness overall. Given stereotypical sex roles, the reproductive success of the focal male is limited only by the number of mates that he can acquire. In other words, while a focal females is always limited to producing n offspring, the number of offspring that a focal male sires increases with every new mating.

Inbreeding therefore increases a focal male’s inclusive fitness directly, instead of indirectly as is the case for focal females. This direct component is n(1 − δ) – the number of offspring sired scaled by inbreeding depression. The focal male also receives an indirect component of 1/8n(1 − δ), which represents the direct fitness of the focal male’s cousin scaled to his relatedness to her (1/8). Note that the inclusive fitness accrued from inbreeding is the same for the focal male as it was for the focal female, the direct plus indirect components of inclusive fitness are n(1 − δ)+1/8n(1 − δ), which can be re-written as n(1 + 1/8)(1 − δ). But if the focal male avoids inbreeding, he has missed out on the opportunity to produce additional offspring – the only consolation is that the cousin he avoided inbreeding with will then outbreed and produce healthy related offspring that benefit him indirectly (note, the focal male might go off and mate with other females, but, given stereotypical sex roles, we’re assuming that he could have done so even if he had chosen to inbreed). His inclusive fitness resulting from the decision to avoid inbreeding is therefore (1/8)n – i.e., his cousin’s inclusive fitness scaled to his relatedness to her. We can contrast the inclusive fitness accrued from inbreeding with that of outbreeding for the focal male, as we did for his cousin,

n (1 - δ) + 1/8 n (1 - δ) > 1/8 n.

Note again, the only difference here is the right-hand side of the inequality (representing inbreeding avoidance), which is now 1/8n to reflect the indirect component of inclusive fitness from avoiding inbreeding. As with the focal female, we can solve for δ to identify the threshold value below which inbreeding yields a higher inclusive fitness than avoiding inbreeding,

n (1 - δ) + 1/8 n (1 - δ) > 1/8 n

(1 - δ) + 1/8 (1 - δ) > 1/8

1 - δ + 1/8 - 1/8 δ > 1/8

1 + 1/8 - 1/8 > δ + 1/8 δ

1 > δ + 1/8 δ

1 > δ(1 + 1/8)

1 / (1 + 1/8) > δ

δ < 8/9.

Here, the focal male increases his inclusive fitness more by inbreeding with his cousin than by avoiding inbreeding with her if δ is less than eight ninths – or if his inbred offspring have a 1/9 probability of survival. Not only does this demonstrate that a focal male can increase his inclusive fitness by inbreeding, it shows that his threshold value of inbreeding upon encountering a cousin is considerably higher than hers. Consequently, sexual conflict over inbreeding is predicted during such an encounter; a focal male will increases his inclusive fitness by inbreeding, while a focal female will increase her inclusive fitness by avoiding inbreeding. In the case of the two cousins, such a conflict is predicted when inbreeding depression satisfies 1/9 < δ < 8/9.

General theoretical insights of Parker’s model

The theoretical insights provided by this simple model are general to encounters between females and males of any given relatedness r:

Natural selection should make inbreeding between females and males adaptive given sufficiently low inbreeding depression in the fitness of their offspring, and females and males will typically disagree over how low inbreeding depression should be before inbreeding is adaptive (generating sexual conflict over inbreeding)

The generality of these two key insights of Parker (1979) can be shown by simply substituting a specific value of relatedness (1/8, in our example with cousins) with r. The general inequality predicting whether or not a focal female’s inclusive fitness increases by inbreeding is thereby modelled as,

n(1+r)(1-δ) > n.

From the above, the general threshold of δ below which a focal female increases her inclusive fitness can be written as,

δ < r / (1 + r).

The equivalent general inequality predicting whether or not inbreeding increases inclusive fitness for males is,

n(1+r)(1-δ) > rn.

For the above, we get the general threshold δ,

δ < 1 / (1 + r).

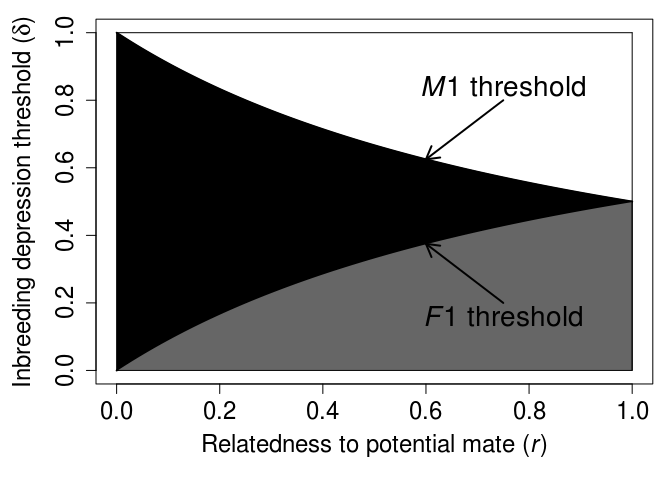

We can plot this threshold δ over a range of r values for both females and males (as appears in Waser, Austad, and Keane 1986; Puurtinen 2011; Szulkin et al. 2013; Duthie and Reid 2015).

Figure 1: Threshold inbreeding depression values below which inbreeding increases female and male inclusive fitness for different relatedness values, as recreated from Duthie and Reid (2015). The x-axis shows the relatedness (r) between two focal potential mates, and the y-axis shows the magnitude of inbreeding depression below which inbreeding is beneficial for each sex. The white shaded region shows where neither sex benefits by inbreeding, the black shaded region shows where only males benefit by inbreeding (sexual conflict), and the grey shaded region shows where both females and males benefit by inbreeding.

Why and how Parker’s insights remain important

The general equation identifying inbreeding depression thresholds for females and males appears in various forms in subsequent theoretical papers including, Waser, Austad, and Keane (1986), Lehmann and Perrin (2003), Parker (2006), Kokko and Ots (2006), Puurtinen (2011), Szulkin et al. (2013), Duthie and Reid (2015), Lehtonen and Kokko (2015), and Duthie, Lee, and Reid (2016). Each of these papers builds off of the foundational work of Parker (1979) in different ways to develop new theoretical insights, clarify existing insights, or unify inbreeding theory with other theory in evolutionary ecology. I’ll save these insights for a future post, and for now just note that the inbreeding depression thresholds of the above model need to be interpreted with caution. The main theoretical contribution of Parker (1979) was to introduce the two theoretical predictions mentioned above concerning the possibility of adaptive biparental inbreeding and expectation of sexual conflict. Parker (1979) did this by showing how these two predictions follow logically from a small number of useful biological assumptions, thereby demonstrating how to think more clearly about inbreeding and inbreeding avoidance in and across natural systems. It is this greater clarity of thought that is most relevant for developing empirical hypotheses, not the specific numerical predictions of inbreeding depression thresholds derived from the above inequalities (as see in the Figure 1 above). Subsequent theory by, e.g., Waser, Austad, and Keane (1986), Kokko and Ots (2006), and Duthie and Reid (2015) builds off of Parker (1979) to show that the numerical values of these thresholds will change depending on additional assumptions about interacting females and males.

Some biological assumptions are expected to apply to all, or nearly all, biological systems. As a theoretician, it is usually most exciting to discover novel predictions that follow from these universal assumptions [5], and to thereby develop theory of the most general relevance that conceptually unifies across the biological sciences. But biological systems vary widely, making it is necessary to also vary the assumptions of our models when deriving system specific – and particularly quantitative – predictions. A lot of relevant biological assumptions about interacting females and males will vary (e.g., as a consequence of life history, other social interactions, direct costs of behaviour, etc.), and these assumptions might plausibly affect the conditions under which inbreeding versus inbreeding avoidance will be adaptive for any particular organism.

[1] As an aside, this is a wonderful book that also includes a chapter written by Bill Hamilton on wing dimorphism in male fig wasps, likening male-male competition within a fig to ‘‘a darkened room full of jostling people among whom, or else lurking in cupboards and recesses which open on all sides, are a dozen or so maniacal homicides armed with knives’’ (Hamilton 1979, 173).

[2] Parker (1979) considered an encounter between a female and her full-sibling brother. I’m going to use cousins to deliberately produce an example with a different numerical result.

[3] Specifically, her coefficient of relatedness; see, e.g., Michod and Anderson (1979) or Duthie and Reid (2015) for more detail on how relatedness is calculated, particularly given inbreeding.

[4] One way to think about this is that for any copy of an allele that the focal female carries, the probability that her cousin will carry a replica copy of this allele due to common ancestry (i.e., a copy that is identical-by-descent, originating in a common ancestor – in this case, a grand-parent) is 1/8. Inclusive fitness predicts that natural selection will act in the direction of increasing replica allele copies, whether they are in a focal indivual or its relative (Hamilton 1964a; Hamilton 1964b). Hence, we need to weigh the reproductive success of a focal female’s cousin accordingly because he is affected by her decision to inbreed or avoid inbreeding.

[5] Or, perhaps equally appealing, to discover previously unknown assumptions from consistently observed patterns (predictions) – or to discover new and interesting paths by which the two are logically connected.

References

Charlesworth, Brian, and Deborah Charlesworth. 1999. “The genetic basis of inbreeding depression.” Genetical Research 74 (3): 329–40.

Charlesworth, Deborah, and John H Willis. 2009. “The genetics of inbreeding depression.” Nature Reviews Genetics 10 (11): 783–96. doi:10.1038/nrg2664.

Duthie, A Bradley, and Jane M Reid. 2015. “What happens after inbreeding avoidance? Inbreeding by rejected relatives and the inclusive fitness benefit of inbreeding avoidance.” PLoS One 10 (4): e0125140. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0125140.

Duthie, A Bradley, Aline M Lee, and Jane M Reid. 2016. “Inbreeding parents should invest more resources in fewer offspring.” Proceedings of The Royal Society B, 20161845. doi:10.1098/rspb.2016.184.

Grafen, Alan. 2006. “Optimization of inclusive fitness.” Journal of Theoretical Biology 238 (3): 541–63. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.06.009.

Hamilton, William D. 1964a. “The genetical evolution of social behaviour. I.” Journal of Theoretical Biology 7 (1): 1–16. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5875341.

———. 1964b. “The genetical evolution of social behaviour. II.” Journal of Theoretical Biology 7 (1): 17–52. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5875340.

———. 1979. “Wingless and fighting males in fig wasps and other insects.” In Sexual Selection and Reproductive Competition in Insects, edited by Murray S Blum and Nancy A Blum, 167–220. New York: Academic Press, Inc.

Kokko, Hanna, and Indrek Ots. 2006. “When not to avoid inbreeding.” Evolution 60 (3): 467–75.

Lehmann, Laurent, and Nicolas Perrin. 2003. “Inbreeding avoidance through kin recognition: choosy females boost male dispersal.” American Naturalist 162 (5): 638–52. doi:10.1086/378823.

Lehtonen, Jussi, and Hanna Kokko. 2015. “Why inclusive fitness can make it adaptive to produce less fit extra-pair offspring.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B 282: 20142716.

Michod, Richard E, and Wyatt W Anderson. 1979. “Measures of genetic relationship and the concept of inclusive fitness.” American Naturalist 114 (5): 637–47. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2460734.

Parker, Geoff A. 1979. “Sexual selection and sexual conflict.” In Sexual Selection and Reproductive Competition in Insects, edited by Murray S Blum and Nancy A Blum, 123–66. New York: Academic Press, Inc.

———. 2006. “Sexual conflict over mating and fertilization: an overview.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 361 (1466): 235–59. doi:10.1098/rstb.2005.1785.

Puurtinen, Mikael. 2011. “Mate choice for optimal (k)inbreeding.” Evolution 65 (5): 1501–5. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01217.x.

Szulkin, Marta, Katie V Stopher, Josephine M Pemberton, and Jane M Reid.

- “Inbreeding avoidance, tolerance, or preference in animals?” Trends in Ecology & Evolution 28 (4). Elsevier Ltd: 205–11. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2012.10.016.

Vogler, Donna W, and Susan Kalisz. 2001. “Sex among the flowers: the distribution of plant mating systems.” Evolution 55 (1): 202–4. doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2001)055.

Waser, Peter M, Steven N Austad, and Brian Keane. 1986. “When should animals tolerate inbreeding?” American Naturalist 128 (4): 529–37.