Pointers In C For Scientists

Working with

arrays of data

(e.g., numeric vectors and matrices) is routine for scientific

researchers doing statistics or modelling. In programming languages with

which most researchers are probably familiar (e.g.,

R, python, and

MATLAB), setting values

into some sort of array is straightforward. In R, we can define a vector

data_vec with one line of code.

data_vec <- c(3, 5, 4, 1, 7, 6);

print(data_vec);

## [1] 3 5 4 1 7 6

We can similarly define a two by two dimensional matrix.

data_mat <- matrix(data = c(3, 5, 4, 1, 7, 6), nrow = 2, ncol = 3);

print(data_mat);

## [,1] [,2] [,3]

## [1,] 3 4 7

## [2,] 5 1 6

In C, this kind of assignment doesn’t work, which can be intimidating at first for researchers new to the language. Instead, memory needs to be allocated appropriately using pointers, which identify where in a computer’s memory variables are located. Thinking about and using pointers effectively can take a bit of getting used to, but being able to use C to do so can massively speed up computations [1], making the investment worthwhile for researchers doing computationally intense statistical or simulation modelling. The intended audience of this post includes researchers who are newcomers to using C, or might be interested in learning C as a means to speed up their analyses, perhaps through integration with R (more on this in a future post). I’m not going to focus so much on how to code in C, but rather the logic of what pointers are and how they are used in the language, as this is a major learning curve when getting started.

All variables initialised in C need to be stored in some address in the computer’s memory. We can think about the memory of a computer as a large block of locations where information can be stored. Each location specifies a single byte, and blocks of bytes are used to store numeric values (Dennis Kubes discusses Basics of memory addresses in C in more detail). If we tell C to print off a set of locations, these are the kinds of values we get.

| Location 1 | Location 2 | Location 3 | Location 4 | Location 5 | Location 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0x7fc010 | 0x7fc011 | 0x7fc012 | 0x7fc013 | 0x7fc014 | 0x7fc015 |

The numbers above are in

hexidecimal, as indicated

by the 0x at the start of each. The numbers therefore start from

7fc010 at Location 1 and end at 7fc015 at Location 6. To make it easier

to conceptualise, we can just replace these with their equivalent values

in base 10.

| Location 1 | Location 2 | Location 3 | Location 4 | Location 5 | Location 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8372240 | 8372241 | 8372242 | 8372243 | 8372244 | 8372245 |

So we have a block of addresses where variable values can be stored.

This is all that we get to work with in C. There is no inherent

structure for representing arrays in C, so if we want to put numbers

into an array of one or more dimensions, then we need to create an array

ourselves. We can do this in C is using the malloc function in the C

standard library to

set aside blocks of memory for multiple numeric values. I’ll get to how

to do this below, but first I need to explain how pointers are

initialised in C. When assigning a single number to a variable, it is

not necessary to allocate memory explicitly. For example, we can define

an integer int variable_1 and assign it to a value of

variable_1 = 10. The very short

program

below does this and prints out a value of 10 before exiting.

#include<stdio.h>

int main(void){

int variable_1;

variable_1 = 3;

printf("\n Value of variable_1 is %d \n", variable_1);

return 0;

}

The #include<stdio.h> tells the

compiler to add the necessary

code for standard input and output functions (in this case printf),

and the program is compiled by running the below on the command line

from within the directory that the program is saved.

gcc -Wall variable_eg.c -o variable_eg

The program variable_eg that is produced by compiling the above is run

below.

./variable_eg

And the output of the variable_eg is shown below.

Value of variable_1 is 3

Storing the values of a one-dimensional array

The above is simple enough for storing a single number, but if we want

to store an array, we need to initialise a pointer – that is, a

variable that contains an address in the computer’s memory. This

address will ‘point’ to the location of the values of interest;

specifically, it will point to the first location in a block of

addresses that can store multiple numeric values. Each element in the

array will occupy a single address. To initialise a pointer, we need to

use the dereference

operator, which in

C is an asterisk (this might seem confusing at first because *

performs two functions in C – dereferencing and multiplying, but the

context makes it easy to tell the two uses apart). When seeing an

asterisk in front of a variable, it can be read as ‘the value at’, so

*pointer_1 is ‘the value at location pointer_1’. We can intialise a

pointer of data type

double in C as follows [2].

double *pointer_1;

We can think of the above instruction as ‘initialise a value of type

double at location pointer_1’. To start assigning numbers to an array,

we need to define how many blocks of size double need to be allocated

using the function malloc. As an example, we’ll start with a simple

one dimensional array of size 6.

pointer_1 = malloc(6 * sizeof(double));

In the above, we’ve told C to allocate a block of memory starting at the

location pointer_1, and extending to a length the size of six double

values. The sizeof operator, as you might expect, returns a

value indicating how much memory

the data type takes to store. This will allow us to place six double

values in a vector at a location in the memory starting at pointer_1.

For the sake of argument, let’s assume that pointer_1 = 8372240, and

so equals the same address as in the earlier example.

| Location 1 | Location 2 | Location 3 | Location 4 | Location 5 | Location 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Address | 8372240 | 8372241 | 8372242 | 8372243 | 8372244 | 8372245 |

Note that 8372240 is the address of pointer_1 in Location 1; the

value at this location is *pointer_1 (which we haven’t yet

assigned). Using malloc in the code above, we have allocated the six

locations 8372240-8372245 for use in our array. If we want to assign a

value in the location, we can use the dereference operator.

*pointer_1 = 3;

The value stored in location pointer_1 is now 3. To store values in

the other five locations that we’ve allocated for use, we can simply add

one to the value of the location with the dereference operator. In this

case, the address of Location 2 in the table above is simply one

more than the value of pointer_1 itself, pointer_1 + 1. So we can

put a value in this location in the same way by indicating the correct

address.

*(pointer_1 + 1) = 5;

The above stores the value five in Location 2 of the example table

above. On the left hand side of the equation, we can read this as the

‘value at the location pointer_1 plus one’. The parentheses tells C to

compute pointer_1 + 1 before applying the dereference operator, so the

correct address is identified within parentheses and dereferenced with

the asterisk outside of them. We can assign six random values and print

them using the function

below

(the standard library stdlib.h includes code needed for memory

allocation functions malloc and free).

#include<stdio.h>

#include<stdlib.h>

int main(void){

int i;

double *pointer_1;

pointer_1 = malloc(6 * sizeof(double));

*pointer_1 = 3;

*(pointer_1 + 1) = 5;

*(pointer_1 + 2) = 4;

*(pointer_1 + 3) = 1;

*(pointer_1 + 4) = 7;

*(pointer_1 + 5) = 6;

for(i = 0; i < 6; i++){

printf("%f\n", *(pointer_1 + i));

}

free(pointer_1);

return 0;

}

We can represent the above in a table again below that includes address

and values stored in each address, using the pointers to represent the

addresses of variables but keeping in mind that each increment of

pointer_1 corresponds to some integer number that maps to a block of

the computer’s memory.

| Location 1 | Location 2 | Location 3 | Location 4 | Location 5 | Location 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Address | pointer_1 + 0 | pointer_1 + 1 | pointer_1 + 2 | pointer_1 + 3 | pointer_1 + 4 | pointer_1 + 5 |

| Value | 3 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 6 |

After allocating memory with malloc, it is important to free the

memory using free when it is no longer needed to avoid a memory

leak. A memory leak occurs

when addresses are allocated but not freed, and the number of available

places to store data decreases. Upon freeing memory, new values could be

stored in the addresses above.

Note how there are six elements in the array, but the last element in

the array is *(pointer_1 + 5) because the array effectively starts at

*(pointer + 0). Arrays in C are zero

indexed; the first

element starts with zero and ends with a value of one less than the

total length of the array. This takes some getting used to for many

researchers who learned to code in R, but it also makes the logic of

for loops a bit more intuitive, as is clear from the function above.

This also brings me to the short-hand bracket notation for using arrays

in C. An easier way to write *(pointer_1 + element) is simply

pointer_1[element].

Hence, we can usually think about an array that we create in C as if

array_1[i] means ‘the ith element of the array array_1’, but it

it’s useful to keep in mind that what it really refers to is ‘the

value at the memory location array_1 + i’. With this in mind, we can

re-write the above

program

as follows, swapping the variable name pointer_1 with array_1.

#include<stdio.h>

#include<stdlib.h>

int main(void){

int i;

double *array_1;

array_1 = malloc(6 * sizeof(double));

array_1[0] = 3;

array_1[1] = 5;

array_1[2] = 4;

array_1[3] = 1;

array_1[4] = 7;

array_1[5] = 6;

for(i = 0; i < 6; i++){

printf("%f\n", array_1[i]);

}

free(array_1);

return 0;

}

The above certainly looks a bit cleaner. The usefulness of the short-hand bracket notation becomes even clearer when working with multi-dimensional arrays, which I will briefly discuss next.

Multi-dimensional arrays in C

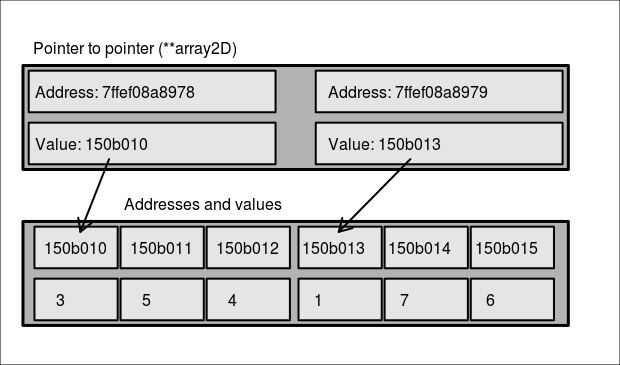

Like one-dimensional arrays, there is no built-in way to tell C that we want to make a multi-dimensional array; we need to use pointers. Even more complicated, there is also no simple way to tell C which pointers should correspond to which dimensions of our array, so we need to remove ourselves yet another level from the actual array element values and define pointers to pointers. For example, if we want to allocate memory into a two dimensional array, we need to define a pointer that points to the first address where we want each row [3] to be. So let’s say that instead of making a one dimensional array of six elements, what we really want is a two dimensional array with two rows and three columns. To do this, we need to first allocate memory to hold a set of pointers, and have each of those pointers hold values that themselves are pointers to where we want the start of each row in our array to be. I’ve drawn this one out below in hopes of making things clearer.

In the above, the pointer to a pointer **array2D is a variable that

holds two values at addresses 7ffef08a8978 and 7ffef08a879. The two

values it holds are 150b010 and 150b013, which are the addresses of

the element in the first column of the first and second rows of the

array. The values stored by **array2D are the addresses of

*(array2D + 0) and *(array2D + 1). So the array will look like the

below.

| Column 1 | Column 2 | Column 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Row 1 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| Row 2 | 1 | 7 | 6 |

To walk through what has happened once more verbally, we have

initialised a pointer to a pointer **array2D of length 2. This pointer

to a pointer stores two values that correspond to the addresses of the

first element of each row of the array. Each row of the array then holds

3 values for each column; to get this to work, we have to allocate

memory for each row separately, which can be done using the code

below.

#include<stdio.h>

#include<stdlib.h>

int main(void){

int row, col;

int row_number, col_number;

double **array2D;

row_number = 2;

col_number = 3;

array2D = malloc(row_number * sizeof(double *));

for(row = 0; row < row_number; row++){

*(array2D + row) = malloc(col_number * sizeof(double));

}

*(*(array2D + 0) + 0) = 3;

*(*(array2D + 0) + 1) = 5;

*(*(array2D + 0) + 2) = 4;

*(*(array2D + 1) + 0) = 1;

*(*(array2D + 1) + 1) = 7;

*(*(array2D + 1) + 2) = 6;

for(row = 0; row < row_number; row++){

for(col = 0; col < col_number; col++){

printf("%f\t", *(*(array2D + row) + col) );

}

printf("\n");

}

for(row = 0; row < row_number; row++){

free(*(array2D + row));

}

free(array2D);

return 0;

}

In the above, malloc(row_number * size(double *)) tells C that we’re

allocating memory to store row_number pointers to double values. In

the first for loop immediately below, we allocate col_number values

of size double for each *(array2D + row), blocking off an

appropriate amount of memory for the length of each row. Note that when

freeing the allocated memory, we can’t just use free(array2D). Since

we allocated memory for array2D and each row *(array2D + row),

we need to free each chunk of memory allocated. Further, memory

allocation to the individual rows must be freed before array2D is

freed, or else C won’t be able to find *(array2D + row) addresses to

free them.

I assigned values to array elements without using brackets to break down what’s going on in terms of pointers, but in practice it is much easier to write this with brackets again.

#include<stdio.h>

#include<stdlib.h>

int main(void){

int row, col;

int row_number, col_number;

double **array2D;

row_number = 2;

col_number = 3;

array2D = malloc(row_number * sizeof(double *));

for(row = 0; row < row_number; row++){

array2D[row] = malloc(col_number * sizeof(double));

}

array2D[0][0] = 3;

array2D[0][1] = 5;

array2D[0][2] = 4;

array2D[1][0] = 1;

array2D[1][1] = 7;

array2D[1][2] = 6;

for(row = 0; row < row_number; row++){

for(col = 0; col < col_number; col++){

printf("%f\t", array2D[row][col] );

}

printf("\n");

}

for(row = 0; row < row_number; row++){

free(array2D[row]);

}

free(array2D);

return 0;

}

Conveniently, we can read array2D[1][2] = 6 as ‘row 1, column 2 of

array2D equals six’, but as with the one dimensional array example, it

helps to remember that we are using the dereference operator twice to

find the location at which the value is located.

A quick note about ‘&’

In most introductions to pointers, the ampersand & operator is

introduced alongside the asterisk *. I’ve not done so here because

most code for simple scientific computing doesn’t really need it (I’ve

only used it a handful of times in several years of coding in C), but I

should mention how it is used. The & identifies the address of a

variable, so we can read &variable_1 as ‘the address of variable_1’.

So, for example, if we set variable_1 = 3, we could set the pointer

*ptr_variable_1 to equal the address of variable_1, &variable_1.

#include<stdio.h>

int main(void){

int variable_1, *ptr_variable_1;

variable_1 = 3;

ptr_variable_1 = &variable_1;

printf("Value of variable_1 is %d \n", variable_1);

printf("Address of variable_1 is %d \n", &variable_1);

printf("Value of ptr_variable_1 is %d \n", ptr_variable_1);

return 0;

}

The above code prints the below.

Value of variable_1 is 3

Address of variable_1 is 0x7fff17e1b3fc

Value of ptr_variable_1 is 0x7fff17e1b3fc

Note that we have set the value of ptr_variable_1 to address

variable_1.

Concluding remarks

This was just a very brief introduction to the logic of pointers and how to use them to make arrays in C. It is not everything you need to know about pointers, but a starting point for being able to work with data in C. My hope is that this explanation will complement other introductions to pointers in a way that will be especially useful for scientists who do not come from a computing background, and who have perhaps avoided making the jump to C from languages such as R, python, or MATLAB in part due to the pointers learning curve.

[1] This is especially true for researchers coding in R for computationally intense tasks that include multiple loops. Running an individual-based model can be 10 to 100 times faster in C than it is in R or MATLAB, which I was surprised to find out while writing the code for what would become the first chapter of my doctoral dissertation. Since then, I do about half my coding in R, shifting to C whenever something needs to run fast.

[2] Double is a precise type of value that can

represent real numbers appropriately for most tasks in scientific

computing. If only integer values are needed, use int instead, which

is exact and uses less memory.

[3] Technically, it doesn’t necessarily have to be the first element of the row, but I usually do this way out of habit.