Unified Theory Of Evolution

Author’s Note: This post was inspired by a recent discussion at the PEGE Journal Club at the University of Stirling. A version of this post also appears on the journal club website.

Conceptual unification of disparate phenomena is a major goal of theory in the natural sciences, and many of the most revolutionary scientific theories are those that have shown how seemingly disparate ideas and observations follow logically from a single unifying framework. The most momentus of these theories include Newton’s unification of gravity and the laws of planetary motion (Newton 1999), Darwin’s explanations of adaptation and biodiversity as following from natural selection and descent with modification, respectively (Darwin 1859), and Einstein’s general relativity unifying gravity, space, and time (Einstein 1911). In all of these examples, theory changed how scientists understand the world by revealing a fundamental concept, the consequences of which affected an entire field of study.

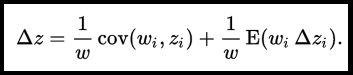

Perhaps to this list of discoveries we should include the unifying equation of George Price (1970) [1], which, in a recent paper in the American Naturalist, David Queller argues to be the most fundamental theorem of evolution (Queller 2017). The Price equation as a unifying framework has been a subject of recent interest both within evolutionary biology (e.g., Grafen 2015b; Frank 2012; Luque 2017) and across disciplines from mechanics (Frank 2015) to music (MacCallum et al. 2012). At its core, the Price equation is a unifying framework for understanding any correlated change between any two entities. Queller (2017) proposes it to be fundamental because it encompasses all evolutionary forces acting on a population, and because it can be used to derive other less general equations in population and quantitative genetics, all of which require stricter assumptions about the evolutionary forces and environmental conditions affecting entities in the population. The Price equation includes two terms to describe the change in any trait Δ z.

The first term islolates how a trait (z) covaries with fitness (w) for entities (i), and encompasses the evolutionary processes of natural selection and genetic drift. The second term encompasses everything else that affects trait change (often called the ‘transmission bias’), such as mutation, selection at within-entity scales, or background changes in environment. Interpreting the Price equation can be a bit daunting at first, perhaps in part because of how abstract the entities (i) are – representing anything from alleles, to unmeasured genotypes, to organisms, to even groups of organisms as the situation requires. Likewise, traits (z) can be any aspect of phenotype associated with such entities, including fitness (w) itself.

It’s here where Queller’s (2017) synthesis really shines, as he carefully walks the reader through how Price’s abstract equation can be used to derive multiple other less fundamental equations in which variables represent something concrete and measureable in empirical populations. These equations include Fischer’s (1930) average excess equation describing allele frequency change in population genetics, the Robertson (1966) and breeder’s equations (Lush 1937) of trait change in quantitative genetics, and Fischer’s (1930) fundamental theorem of natural selection. In all cases, Queller (2017) notes the additional assumptions that are required to use these equations, particularly that the second term of the Price equation equals zero meaning that no transmission bias exists. The end result is a synthesis that organises a set of equations that are familiar to evolutionary biologists in a way that follows logically from the fundamental equation of Price.

Future directions for conceptual unification (work in progress)

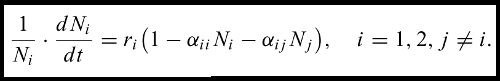

The recent interest in the Price equation is encouraging for the further theoretical unification of the biological sciences, and Queller’s (2017) paper nicely complements a more philosophical analysis by Victor Luque (2017). It’s important to keep in mind that the Price equation is, at its core, about correlated change between entities, and its application is not restricted to changing alleles or phenotypes. It can be applied equally well to non-biological entities if need be – Price himself proposed the example of selecting radio stations with a turning dial (Gardner 2008). Even within biology though, there seems to be scope for further conceptual unification, particularly between evolution and ecology. Extensions of the Price equation allow for selection across different levels of biological organisation and different classes within a population (Heisler and Damuth 1987; Grafen 2015b; Rankin et al. 2015; Queller 2017). Entities in the Price equation might therefore represent individuals grouped according to class or species, with fitness (w) defined by individual or group reproductive value (Williams 1966; Grafen 2015a) and the trait of interest (z) being, for example, group abundance. There is no reason that this wouldn’t work in principle; the Price equation can handle covariation between any two traits, so a link between individual reproductive value and group abundance should be possible. From here, it might be possible to derive not just the fundamental equations of population and quantiative genetics, but potentially fundamental equations of population and community ecology, such as the modern version of Lotka-Volterra competition below as appears in Chesson (2000b).

How to get from the Price equation to Chesson’s version of the Lotka-Volterra equation immediately above in a way that unifies ecological and evolutionary dynamics isn’t immediately obvious to me. Page and Nowak (2002) provide an interesting link between the Price equation and classical Lotka-Voltera dynamics through game theory. They note, essentially, that different species can be intepreted as different strategies whose fitness payoffs (in terms of reproductive rates) depend on the abundance of other strategies. They then show that the game-theoretic interpretation of Lotka-Volterra is equivalent to a continuous time version of the Price equation. The first term of the Price equation still describes selection, while the second term of the Price equation includes changes in a trait value (which can be interpreted as species abundance) caused by a varying environment or interactions between species (they also include a third term describing among-type mutation). Page and Nowak (2002) do not break the equation down any further, but there would seem to be scope for expanding the second term of the Price equation to isolate the effects of species interactions on species abundance, perhaps as driven by environmental fluctuation (e.g., Chesson 1982; Chesson 1994; Chesson 1985; Chesson 2000a). Interestingly, Queller (2017) suggests that there might ‘‘also be candidates for fundamental-theorem status derived from the second term’’. I don’t yet know whether or not this is the case, but it would certainly be interesting if many fundamental theorems of population and community ecology could be derived from the Price equation with the second term doing most of the heavy lifting.

Communicating the fundamental theorem of evolution

The status of the Price equation as a the fundamental theorem of evolution from which all other key equations in population and quantiative genetics can be derived also raises some pedagogical questions. I have taught a course on Biological Evolution to undergraduates a few times now (though not recently), in which students learned both the average excess equation of Fisher (1930) and the breeder’s equation of Lush (1937). These equations were used and discussed in detail in the population genetics and quantitative genetics sections of the course, respectively, but without much attempt to synthesise across the two sub-disciplines. I believe it was particularly challenging for students to shift their thinking from the measured genotypes of population genetics to the more statistical thinking associated with quantitative traits [2]. The Price equation might be useful for giving students a clearer overview of population and quantitative genetics equations and how they relate to one another. I don’t know if this would be best accomplished by explicitly starting off with the Price equation in the way that Queller (2017) does (which would seem daunting to say the least), or perhaps by instead presenting the concept of trait change under different, hierarchically organised, assumptions that can be addressed with different but inter-related equations. However it is accomplished, showing the link between these two sub-disciplines of evolutionary biology would almost certainly improve and reinforce students’ understanding of evolution (Leamnson 2000).

[1] For more information on the history behind the Price equation and the very interesting life of George Price, I recommend The Price of Altruism by Oren Harman. For an introduction to both George Price and further explanation of the Price equation and its importance, see Gardner (2008).

[2] I also recall this shift in thinking to be a bit challenging at first when I was an undergraduate myself. My first introduction to quantitative genetics was in undergraduate evolutionary biology, by which time I was familiar with population genetics and had learned quite a bit of evolutionary ecology. At first I tried to understand the breeder’s equation on these terms, or to find some sort of conceptual link between them, so it took a bit of work for me to understand what was going on with selection on quantitative traits.

References

Chesson, Peter L. 1982. “The stabilizing effect of a random environment.” Journal of Mathematical Biology 15: 1–36.

———. 1985. “Coexistence of competitors in spatially and temporally varying environments: a look at the combined effects of different sorts of variability.” Theoretical Population Biology 28 (3): 263–87. doi:10.1016/0040-5809(85)90030-9.

———. 1994. “Multispecies competition in variable environments.” Theoretical Population Biology 45: 227–76.

———. 2000a. “General theory of competitive coexistence in spatially-varying environments.” Theoretical Population Biology 237: 211–37.

———. 2000b. “Mechanisms of maintenance of species diversity.” Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 31: 343–66.

Darwin, Charles. 1859. The Origin of Species. New York: Penguin.

Einstein, A. 1911. “Einfluss der Schwerkraft auf die Ausbreitung des Lichtes.” doi:10.1002/andp.19113401005.

Fisher, Ronald A. 1930. The genetical theory of natural selection. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Frank, S A. 2012. “Natural selection. IV. The Price equation.” Journal of Evolutionary Biology 25: 1002–19. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2012.02498.x.

Frank, Steven A. 2015. “D’Alembert’s direct and inertial forces acting on populations: The price equation and the fundamental theorem of natural selection.” Entropy 17 (10): 7087–7100. doi:10.3390/e17107087.

Gardner, Andy. 2008. “The Price equation.” Current Biology 18 (5): 198–202. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.01.005.

Grafen, Alan. 2015a. “Biological fitness and the fundamental theorem of natural selection.” American Naturalist 186 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1086/681585.

———. 2015b. “Biological fitness and the Price Equation in class-structured populations.” Journal of Theoretical Biology 373. Elsevier: 62–72. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2015.02.014.

Heisler, I Lorraine, and John Damuth. 1987. “A method for analyzing selection in hierarchically structured populations.” American Naturalist 130 (4): 582–602.

Leamnson, Robert. 2000. “Learning as biological brain change.” Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 32 (6): 34–40.

Luque, Victor J. 2017. “One equation to rule them all: a philosophical analysis of the Price equation.” Biology and Philosophy 32 (1). Springer Netherlands: 1–29. doi:10.1007/s10539-016-9538-y.

Lush, J L. 1937. Animal Breeding Plans. Ames, IA, USA: Iowa State College Press.

MacCallum, Robert M, Matthias Mauch, Austin Burt, and Armand M Leroi.

- “Evolution of music by public choice.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109 (30): 12081–6. doi:10.5061/dryad.h0228.

Newton, Isaac. 1999. The Principia: Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy, A New Translation. Edited by Bernard Cohen and Anne Whitman. Berkley: University of California Press.

Page, Karen M, and Martin A Nowak. 2002. “Unifying evolutionary dynamics.” Journal of Theoretical Biology 219 (1): 93–98. doi:10.1016/S0022-5193(02)93112-7.

Price, George R. 1970. “Selection and covariance.” doi:10.1038/227520a0.

Queller, David C. 2017. “Fundamental theorems of evolution.” American Naturalist 189 (4): 000–000. doi:10.1086/690937.

Rankin, Brian D, Jeremy W Fox, Christian R Barrón-Ortiz, Amy E Chew, Patricia A Holroyd, Joshua A Ludtke, Xingkai Yang, and Jessica M Theodor. 2015. “The extended Price equation quantifies species selection on mammalian body size across the Palaeocene/Eocene Thermal Maximum.” Proceedings Of The Royal Society B 282: 20151097. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2015.1097.

Robertson, Alan. 1966. “A mathematical model of the culling process in dairy cattle.” Animal Science 8 (1): 95–108.

Williams, G C. 1966. “Natural selection, the costs of reproduction, and a refinement of Lack’s principle.” American Naturalist 100 (916): 687–90.